- Details

Australian research into the molecular make-up of cells in the body, common elements, and minerals has reached a milestone with researchers at the Australian Synchrotron releasing detail of their 1000th protein structure to the world, paving the way for improved understanding of disease and more targeted therapies.

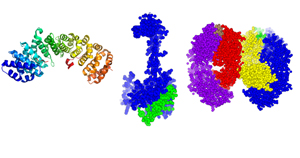

Detailed imagery of the Bax protein (pictured, centre), determined by scientists from the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research in Melbourne using the Australian Synchrotron, was the 1000th structure submitted to the Protein Data Bank, a free and open-access central repository for crucial molecular information that supports global biological research.

Dr Peter Czabotar from the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute says Bax will now be analysed to understand key steps involved in programmed cell death in diseases.

‘Through our experiments at the Australian Synchrotron, we can now picture the molecular structure of Bax and, by analysing its surface, shape and interactions, we can now work toward treatments that support, or block, its activity, depending on its role in different diseases, including cancer.’

Scientists from Australian and New Zealand used the Australian Synchrotron to solve 1,000 protein structures in less than eight years, using only two of the facility’s ten experiment stations, known as beamlines, a rate on par with other, larger synchrotrons in North America, Europe and Asia.

Dr Tom Caradoc-Davies, Principal Scientist of the Macro and Micro-molecular Crystallography (MX1 and MX2) beamlines at the Synchrotron, says the facility is crucial to understanding the structure of proteins, at a molecular level, which cannot be visualised in any other laboratory setting.

‘To reveal a protein’s structure, which may hold the key to better understanding its role in diseases, treatments or industrial products, researchers must purify the protein and turn it into a crystal -- the right crystal can take months to make and may be too small or weak to subject to regular laboratory X-ray research.

‘The Australian Synchrotron’s X-ray light is a million times brighter than the sun, enabling light to diffract off crystals smaller than one-tenth the thickness of a human hair, leading to high definition data sets that can produced in a matter of minutes, rather than days.’

Dr Caradoc-Davies says structures discovered using the Australian Synchrotron have unlocked innovation across a range of scientific fields including medical research, electronics and mining.

‘New appreciation of how proteins are shaped enables scientists to understand their role in the onset and progression of diseases, design novel drugs that target proteins for new medicines, or rationally engineer new medical products.’

Also pictured: the 500th protein deposited to the Protein Data Bank, called 3ZIN (left), solved in 2013 by researchers at The University of Queensland and, (right), a sphere model of Solanezumab, showing every individual atom; insight into how Solanezumab interacts with brain proteins associated with the development of Alzheimer’s highlights what makes current therapies for the disease effective, and show how these therapies can be improved, revealed earlier this year by research from St Vincent’s Institute of Medical Research.

- Details

Research using the Australian Synchrotron to understand how milk is digested, to drive innovation in products that deliver nutrients to infants, received a boost on Friday when a collaborative team from Monash University and the Australian Synchrotron were awarded a Discovery Projects Grant from the Australian Research Council.

The grant, worth $523,000 over 3 years will build on the discovery in March this year that human breast milk forms into highly organised structures at the nanoscale, during digestion in the body.

Monash University’s Professor Ben Boyd (pictured right), a Principal Investigator on the successful grant with Dr Adrian Hawley (pictured left) from the Australian Synchrotron’s Small and Wide X-ray Scattering (SAXS/WAXS) beamline, says delivering new understanding of the processes of milk

‘Milk is the most important food for human survival, providing all the essential nutrition to newborn infants and constituting a major part of the adult diet.’

‘We recently discovered that a nanostructure is formed during the digestion of both cow and breast milk and, through this funding, we will investigate this nanostructure formation as part of a broader effort to develop new food supplements and nutritional formulas that are more easily digested.’

Minister for Education and Training, Senator Simon Birmingham, who announced the funding in Adelaide on Friday as part of the Australian Research Council’s (ARC) Major Grants Announcement, said that the funding is a strong investment in research excellence and the future health of Australian research.

‘A strong investment in high-quality research will drive innovation, secure the jobs of the future, improve the health of our community, protect our environment and ensure our researchers can compete on the international stage.’

Other research projects to be awarded today with close research links to the Australian Synchrotron (Soft X-ray beamline) include the search for more efficient energy generating, storing and transmitting material that will allow a break away from conventional silicon based transistor technology, led by Dr Mark Edmonds from Monash University, and research to create nanotechnologies to sense traces of chemical and biological molecules, to improve air, water and food safety and pharmaceutical and cosmetic products, led by Dr Luhua Li from Deakin University.

- Details

Professor Calum Drummond, Deputy Vice-Chancellor Research and Innovation and Vice-President of RMIT University has been awarded the prestigious Victoria Prize in the Physical Sciences category, honouring his fundamental chemistry research, involving the Australian Synchrotron, that is enhancing industrial products and improving nanomedicine drug delivery for people with cancer.

Professor Drummond's research has led to design rules that were used to invent two patented drug delivery technologies, enabling drugs to be encapsulated in nanostructured material and diffused in a controlled manner to treat cancerous tumours.

The prize, one of two awarded last night at a ceremony in Melbourne, honours Professor Drummond’s contributions to understanding of key factors involved in molecular assembly in liquids, research completed in partnership with scientists on the Small and Wide Angle X-ray Scattering (SAXS/WAXS) beamline at the Australian Synchrotron.

By devising a new method of high-throughput analysis on the SAXS/WAXS beamline, Professor Drummond and his team from RMIT University and CSIRO were able to investigate thousands of liquid and liquid crystal samples a day, greatly increasing the number of known molecules capable of self-assembling in solvents to form materials with ordered 2D and 3D internal nanostructures.

Known as amphiphiles, these molecules can be used to create advanced nanostructured materials, with applications including nanomedicine, environmentally friendly off-shore oil well drilling fluids, waterproof recyclable paper coatings, household cleaning products, and specialty chemicals for the construction industry.

Professor Drummond says he is humbled and delighted to receive the Victoria Prize.

‘I have always been of the mindset that conducting excellent research is necessary but not sufficient, it is what you do with the excellent research to benefit others beyond the academic community that is most important.

‘My research is driven by the desire to innovate and make an impact, through understanding and solving problems faced by industry and the community.

‘It is a great honour for our work to be recognised. Scientific research is a team-based activity and this award also recognises my many research colleagues in CSIRO, RMIT and elsewhere.’

The annual Victoria Prize and Victoria Fellowships recognise the important role innovation plays in the state’s economic future, reinforcing the need for Victorians to be skilled in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM).

Victorian Minister for Industry Lily D’Ambrosio has congratulated the winners of the prestigious awards.

‘Victoria’s reputation in science innovation is truly a testament to the high quality of innovators and researchers that our universities produce.

‘The Andrews Labor Government is committed to supporting Victorians in science, engineering and technology, to research in the areas that will help create industry growth, including local jobs and a stronger economy.’

Also last night, users of the Australian Synchrotron were awarded three of the six Victoria Fellowships in Physical Sciences: Dr Daniel Gomez from CSIRO, Dr Nisa Salim from Deakin University and Alex Schenk from La Trobe University.