In 2008, the following Australian Synchrotron articles appeared in Australasian Science magazine.

An end to lost crystals?

Nearly 100 years ago Australian-born Lawrence Bragg and his father William Bragg invented a way to use x-rays to reveal crystal structures. Today in Melbourne, x-ray crystallography is one of the most important techniques being used at the Australian Synchrotron, with protein chemists and biologists lining up for access.

Proteins are the action molecules of life. As enzymes, they control all biochemical reactions, and they operate by means of their structure. That's why the bulk of research into new drugs and molecular biology nowadays involves determining the structure of proteins - typically using synchrotron x-rays for protein crystallography.

Click here to download the full text (pdf, 50kb) of this article from January/February 2008.

Extreme cooking

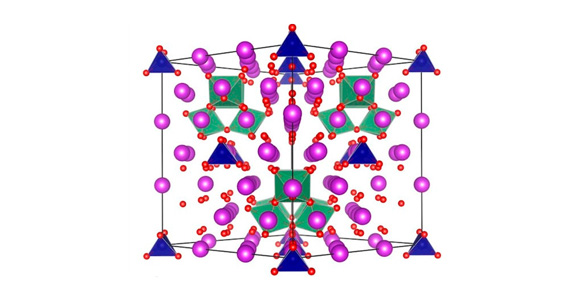

The build-up of scale in your kitchen kettle is annoying but easily fixed. However, you've got a much bigger problem if your kettle is 30 metres high and you're cooking bauxite in caustic soda at high temperature and pressure - like Australia's $12 billion aluminium export industry. Fortunately synchrotron scientists are on the case.

Click here to download the full text (pdf, 50kb) of this article from March 2008.

Soft X-rays: The Swiss Army Knife of Synchrotron Light

The new soft x-ray beamline at the Australian Synchrotron will be contributing to a greener Australia, with users looking at soil structure and 'paint-on' solar panels.

While 'soft' may sound like an odd term for x-rays, it describes their low energy, not their application, according to the scientist in charge of the beamline, Bruce Cowie: "They are the Swiss Army knife of synchrotron radiation because they can be used for so many things".

In particular, Cowie says that soft x-rays are good for investigating the chemistry of surfaces, and also the bonding patterns of the smaller and lighter elements from which living organisms are built.

Click here to download the full text (pdf, 50kb) of this article from April 2008.

Revealing the Mysteries of the Earth's Crust

It might seem at first glance to be one of the simpler techniques performed at theAustralian Synchrotron, but x-ray absorption spectroscopy requires a beamline that is very finely tuned. The technique measures the amount of x-rays absorbed by a sample while scanning a selected range of x-ray energies. The result is information on what elements are present and in what chemical form, what their local environment is and how they are bonded. The technique is only available at synchrotrons.

Click here to download the full text (pdf, 50kb) of this article from May 2008.

A Forensic Look At Synchrotron Light

Forensic scientists have to think fast to keep ahead of criminals educated by CSI and similar television shows. Fortunately, the scientists haven't run out of ideas.

With the help of synchrotron light they are developing ways to detect antique forgeries from the chemical signatures of pigments, drug use from a single hair, and even a person's sex from a fingerprint. Similar techniques are contributing to occupational health and disease diagnosis. In most cases, the testing is non-destructive - an important issue in forensic work.

Click here to download the full text (pdf, 50kb) of this article from June 2008.

The Synchrotron Environment

The brilliant beamlines of the Australian Synchrotron are finding a host of environmental applications, from studying the chemistry of the upper atmosphere to developing better catalysts for hydrogen production.

Detecting and precisely locating specific atoms and molecules is one of the things synchrotrons do best. That makes them very useful for many environmental applications.

Click here to download the full text (pdf, 50kb) of this article from July 2008.

Here's to your Good Health!

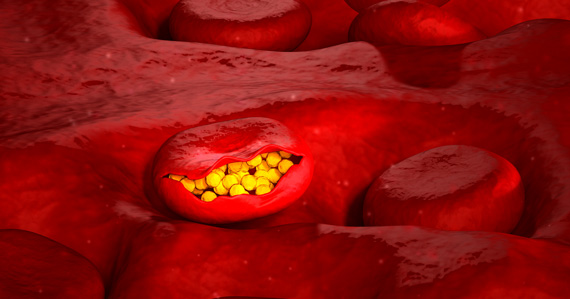

Potentially carcinogenic diet supplements, new drugs for arthritis and plaque formation in arteries are some of the issues that researchers are exploring with the help of synchrotron light.

Click here to download the full text (pdf, 50kb) of this article from August 2008.

Gold, Silver and Green for Synchrotron Scientists

The Australian Synchrotron is solving some intriguing material science challenges.

Click here to download the full text (pdf, 50kb) of this article from September 2008.

SAXS Appeal Reveals a Broken Heart

The latest beamline to reach 'first light' at the Australian Synchrotron uses an intense beam of x-rays that allows researchers to take a wide view and a narrow view of their sample simultaneously. One of its first users will use it to visualise the biochemistry of the beating heart.

Click here to download the full text (pdf, 50kb) of this article from October 2008.

Synchrotron puts people under the beam

When the Australian Synchrotron's Imaging and Medical Therapy beamline opens next year, researchers will be able to follow the movements of individual stem cells. They will be able to follow cancer cell movement and tumour development to eventually develop better treatment.

Already new synchrotron-based radiotherapy techniques are being developed, and will be implemented at the Australian facility to enable clinical research into cancer treatment.

The beam will be 10 million times more intense than a hospital x-ray but will be delivered in tight, sharply-tuned beams. It will expose patients to x-ray doses similar to and in some cases lower than those from conventional machines.

Click here to download the full text (pdf, 50kb) of this article from November/December 2008.